Tim Cook is an amazing public company CEO

. . . but he can’t make Apple a startup for the third time, and neither can anyone else

The recent judicial disaster for Apple has led to a lot of hand-wringing in the tech world about how Tim Cook has done a poor job leading the company, hurt its brand, ceded control of the app store via poor decision making, and other ills. Mixed in with the criticism is the evergreen “Apple can’t innovate anymore” critique. Here’s the thing: this is all true, and Tim Cook is probably the best living public company CEO.

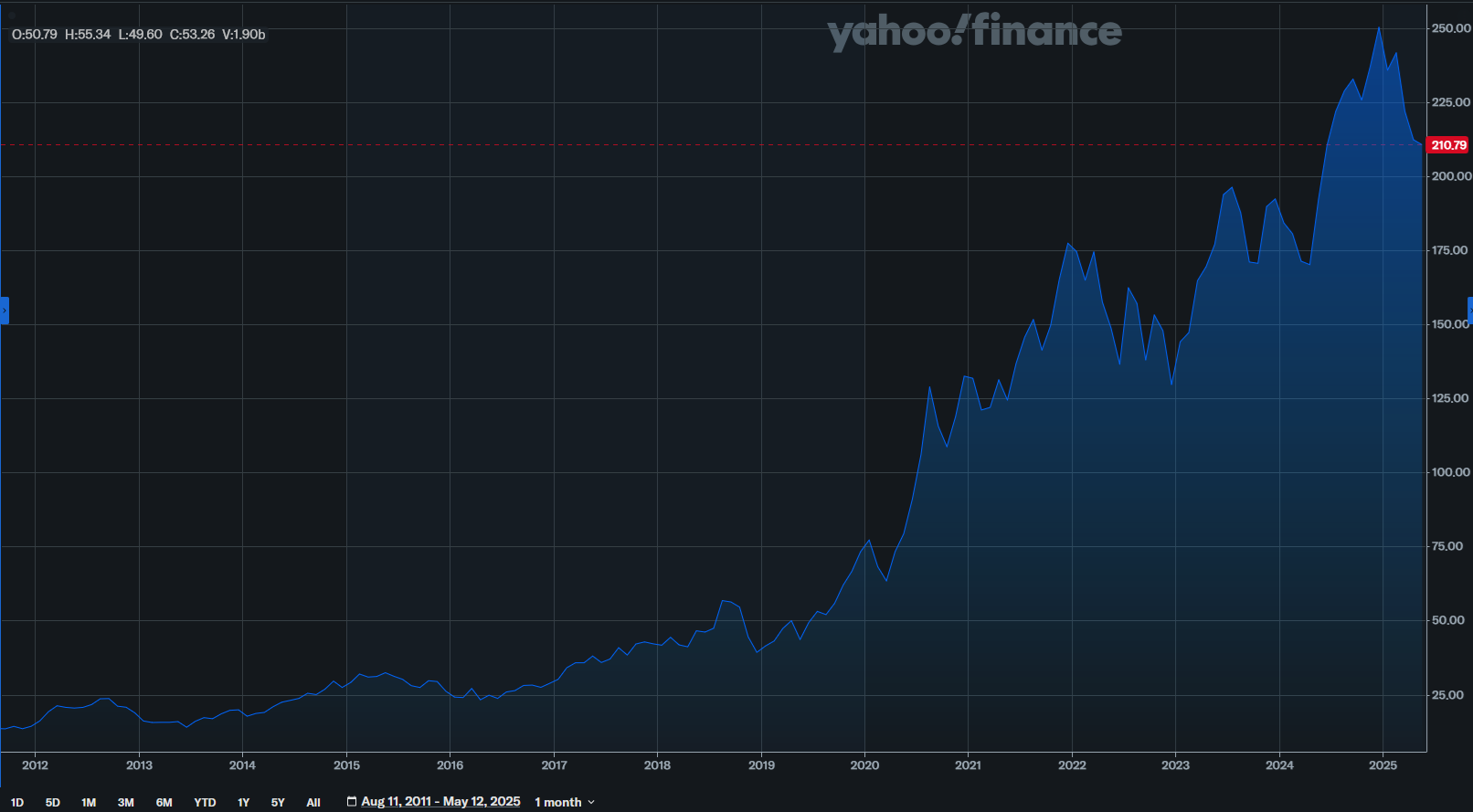

Last week, I was at lunch with an LP who is an enormous Warren Buffett fan, to the extent that he travels to Berkshire’s shareholder meeting every year to attend in-person (and what a year to be there in person). As he told it, at the meeting, Buffett asked Cook to stand up and receive an ovation for generating more value than any other company for Berkshire shareholders. And he’s not wrong. Look at this chart!

That’s Apple’s share price from the day Cook took over to today (or yesterday depending on when I get around to hitting publish). That’s insane! Also, note the scale. This isn’t some clever visual trick: the price went from $14 to over $200 in about a decade. No wonder Buffett made Cook the VIP. We’re talking about a giant public company that hit a mid-20s IRR.

Here is the even more mind-blowing fact: during that entire period, Apple did not create any meaningful new consumer products.¹ All of that: it’s just the iPhone.

Whether intentional or not, Cook behaved as if he had had a remarkably profound insight back in 2011: “we will not do anything like the iPhone ever again, and the way to generate outsized shareholder returns is to figure out how to transfer as much value as possible from this new platform to Apple.”

I’ve read a bunch of criticism that screwing over developers and locking down the platform was short-term thinking—but that thinking got them a mid-20s IRR over thirteen years. That’s . . . not short-term.

There were real downsides, of course. The Vision Pro was stillborn largely because no developer in their right mind wanted to be a serf on another one of Apple’s platform plantations. There was very tepid developer interest, of course. The fees weren’t even the worst part; you had no idea if you might wake up on some fine day and find that, for a completely arbitrary—often inaccurate—reason, Apple has kicked you out of the store. It happened to a portfolio company of ours (they survived only because they were a well-connected ventured-backed company that was able to work their connections and get someone more senior to reverse the error).

They’ve burned up enormous amounts of goodwill with their biggest fans. Go read John Gruber’s latest thoughts and remember that this is a guy whose arguments Steve Jobs once forwarded to an aggrieved customer. Or the guys over at ATP. Or Ars-Apple-fan-zone-Technica.

It’s enough to get you thinking about John Scully. Well. Under John-the-terrible-CEO-Scully, Apple went from $800mm in sales to eight billion.

A startup, again

Steve Jobs’s returning to Apple wasn’t really “rescuing” Apple from a terrible CEO. It was reinventing the company as a startup, except this time with billions of dollars of revenue to play with. Apple should have been Oracle by now, but by a weird quirk of fate, Apple got to be a startup twice and in doing so became the most valuable company in the world.

Scully and Cook were doing what large-company CEOs do: figuring out how to extract maximum value from the things that made the company great. That is what every public company CEO does every day. Squeezing out those profits for thirteen years really is quite the incredible run—compare that to Scully’s mere four years. Buffett was right: Tim Cook is an exceptional public company CEO when measured against the benchmarks used for public company CEOs. Measured against those of a founder, though, his tenure has been a disaster.

Paul Graham’s concept of founder mode has a lot to recommend it, but I think the real benefit of founder mode has more to do with values than management. Just ask Steve:

Values

It is somewhat haunting to listen to Jobs in that video talk about how his successor “ruined it by bringing in a set of values . . . that corrupted some of the top people there” in light of Andrew Roman’s referral for criminal prosecution.

One of his most trenchant insights in that interview is when he says near the end that “they had this wonderful thing that a lot of very brilliant people made called the Macintosh [but] no one there has a clue . . . they’ve just been living off that one thing for a decade.” (!) I mean just replace “Macintosh” with “iPhone” and digitally remaster the video, and it could’ve been recorded yesterday.

(As an aside, I think this is why Phil Schiller was the one advocating against the course of action that Tim Cook chose. He was on the product side, long ago, back in the second Jobs era and has a vague memory of those old values.)

I have come around to thinking that the reason startups are so innovative is simply that there isn’t any other way to succeed in one. They attract people who are obsessed with building things, because financial engineering and market manipulation are simply impossible. Even if founders wanted to behave that way, it wouldn’t work.

Simply put, great startups build great things, and great large companies make lots of money off of those things until they run their engines dry and shrivel up. That isn’t to say the latter is unimportant; 401(k)s don’t fund themselves, and there is no reason to expect companies to last forever. Just don’t expect large companies to act like startups. They cannot attract the kind of talent necessary to remain obessed with building when easier (and more effective) paths to profitability present themselves, and their boards would never tolerate such things.

Except it did happen once. And that company became the most valuable one in the world.

¹ Yeah, yeah, “what about Airpods?” They’re Bluetooth heaphones. They’re entirely an outgrowth of the iPhone; the only reason that they generated so much value is because Apple made the Bluetooth experience with competing headphones terrible. It’s like saying Objective C’s growth in mobile is evidence of some huge innovation by Apple in programming languages.