Entrepreneurship as a downside hedge

It’s the opposite of what you think

Received wisdom has always been that building a startup is a highly risky—perhaps the most risky—career choice one can make. Maybe that was once true, but today, building a startup is the best possible hedge against career risk. I know that sounds crazy, but hear me out.

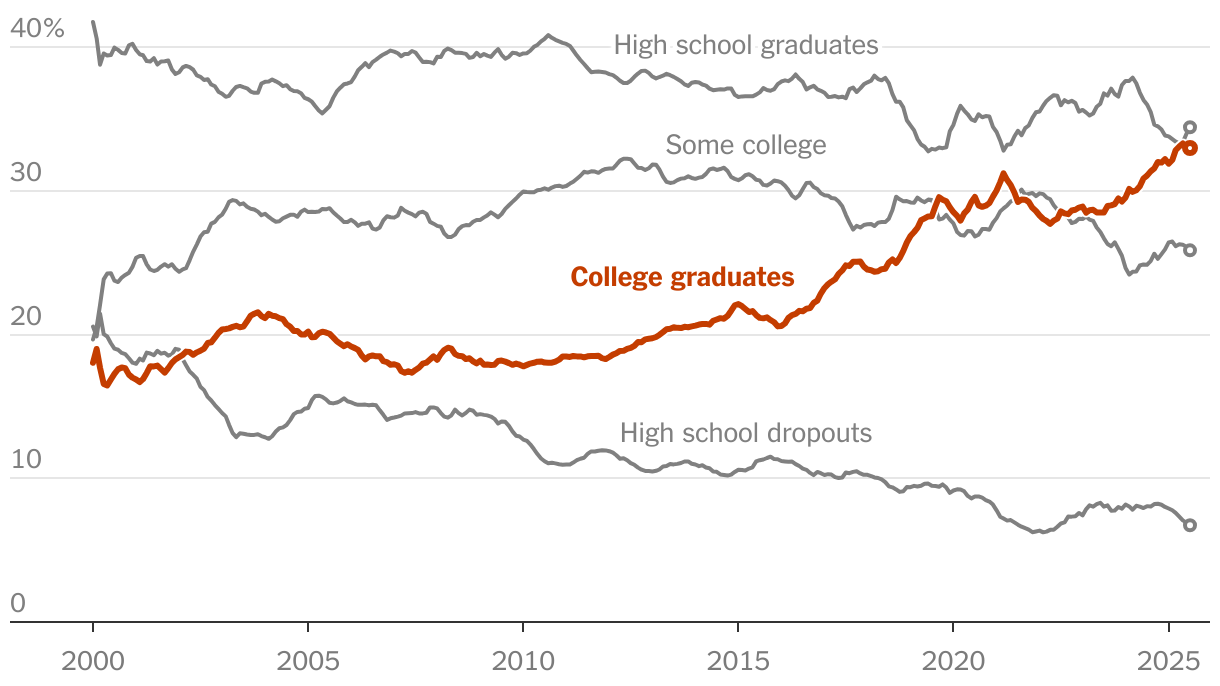

This image, which depicts the share of long-term (>6 months) unemployment by education is absolutely wild:

Chart depicts the change in the distribution of educational degrees held by unemployed people; it does not represent unemployment by category[1]

Chart depicts the change in the distribution of educational degrees held by unemployed people; it does not represent unemployment by category[1]

The entire article is worth a read, but it is hardly controversial to state the plainly obvious point that AI is going to do to knowledge work what automation did to factory jobs. Just as in those factories, the jobs that remain will be better, more productive, and higher paid, but there will be far fewer of them in the economy overall. Still, as the old joke goes, nobody wants to be the person who gets the invisible middle finger from the invisible hand.

Nobody has any idea how this new technology will ripple through the economy. Certainly, some areas will see more disruption than others, but trying to guess which areas will suffer the least disruption is a fool’s errand. Things are moving too quickly.

What we do know with a high degree of certainty, though, is that existing companies are doing a terrible job leveraging AI. Startups, as I discussed a few weeks ago, are the technology’s greatest beneficiaries. They can be nimble and adapt to the changing landscape far faster than any other type of organization.

AI—all technology really—is just leverage, and leverage creates power-law outcomes. Nobody was truly rich when humanity was composed of hunter/gatherers, because being 10% better at gathering didn’t really mean very much. Being 10% better at farming, though, was serious business: technology created the opportunity to produce a surplus. At well-run companies, the top-tier employees make orders of magnitude more than everyone else. At the extreme end, building a 10% better chat app meant it was worth twenty billion dollars.

Nearly everyone is going to have access to these technologies, meaning that the entire knowledge economy is going to become even more exposed to the power law than it already is. AI is going to supercharge the best employees, who are going to do the jobs of ten or a hundred peers.

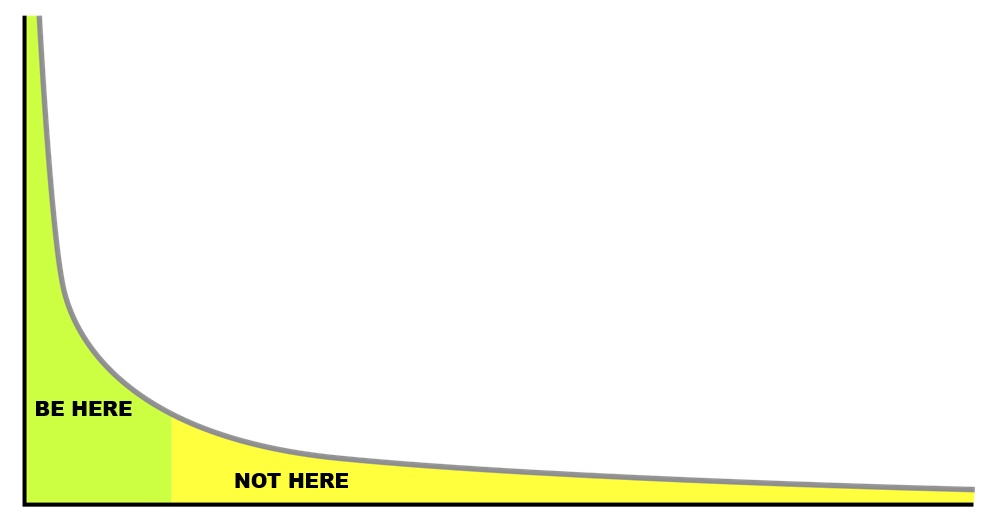

In this scenario, you really want to be left of the knee:

Getting there in a big corporation is going to be exceptionally difficult. Employees will be caught between layoffs on one hand and being forced by non-technical management to use inferior tools in inefficient ways on the other (and then fired anyway, because they’ll be using AI stupidly). Imagine spending the next decade using lousy, in-house AI tools that probably won’t even work, while your peers are starting companies that can build their entire businesses around the latest technology and change as rapidly as the technology can evolve.

In 2025, entrepreneurship is an off ramp from career obsolescence. In the pre-AI world, the resources and training offered by big employers were a significant benefit. In a post-AI world, those resources can be substituted by machines, and the training on obsolete practices and technology is worse than useless. Being your own manager is the only way to adapt quickly enough in this evolving environment.

Even if your startup fails, the opportunities in corporations will be substantially better for employees who can lay claim to understanding how best to use the newest technologies. Instead of being told by the employer what technology to use, an acqui-hired founder is there to tell the employer how to do things better. Sure, relative to an IPO, it’s not the ideal outcome, but my whole point here is that building a startup is no longer a career risk with huge upside; it’s now the safe bet that comes with a side helping of enormous upside.

Especially if you are at the beginning of your career, building the experience of using the best tools in the most efficient way will pay massive dividends throughout your career.

So go start a company (ideally in financial services, since that’s clearly the best place to do it), and call us.

I’m not sure why they used a line graph to show this when something like an area chart would’ve been much more intuitive. The graph is showing what percentage of total long-term unemployment each line represents; it is not showing the unemployment rates for each category. At every point on the X-axis, all of the Y-values will sum to 100%. In any event, the key point is that fewer than 20% of long-term unemployed workers in 2000 had a college degree, but that number has risen to well over 30% today. ↩︎